R19 T83 Resilient Warship

Targets

Dependencies

Background

Type 83 Destroyer

The Type 83 Destroyer, the replacement for the Type 45 Daring Class Destroyer currently in use with the Royal Navy, begins its design phase in 2022 with a planned deployment in the early 2030s.

Under current plans, the RN’s six Type 45 destroyers commissioned between 2009-13 will leave service between 2035 and 2038. Designing and funding their replacements presents a challenging task as the above-water battlespace is becoming increasingly dangerous and complex.

The weapons capability of the T83 is likely to include some form of AI driven Fire Decision Assistance, AI assisted Network-Centric Communications (where there is a shared view of the entire battlespace between all platforms), and Fire Control Handoff (where one ship can effectively fire the weapons of a second ship using data that it has gathered.)

Internally, it's likely that the T83 will follow previous designs with integrated data-only communications system incorporating all activities from satellite, high-frequency radio, radar target aquisition and fire control to secure voice and damage control operations. Likewise it's likely it will follow previous designs in deploying an all electric propusion fitout where there is no direct engine-to-driveshaft connection and therefore relies heavily on that same data network.

As a weapons platform, it's helpful to consider the Type 45 which extended the previous capability by the inclusion of the Sampson Radar system linked to PAAMS (Principal Anti Air Missile System), which is designed to protect an area of sea around a Task Group against high performance threats such as low altitude missile saturation attacks, supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles, fighter aircraft and UAVs. The complement of 48 VLS (Vertical Launch System) Aster missiles available to it is already being considered too small given the military doctrine of both Russia and China, who favour massed anti-ship missile attacks. The fact that the Type 45 successor has been named as Type 83 hints that the T83 will therefore be substantially larger, and likely to have a considerably larger complement of VLS missiles.

On future weapons development over the operational period of the T83, it's likely that a new generation of weapons, notably rail gun systems (which continue to be developed by both China and Russia) hypersonic anti-ship missiles and ballistic anti-ship missiles will increasingly put surface combatants at much greater risk. Any platform that is going to provide credible defence for a Task Group against these threats will inevitably have to be sophisticated, large and substantially more automated in its Fire Control and Operations Functions.

The Royal Navy continues to lead the way in Directed Energy Weapons (DEW) as CIWS (Close-in Weapons Systems), and appears to be on track for deployment mid-2030s. Although rail gun development in NATO has stalled, USN, China and Russia continue to develop hypersonic missiles, and with previous agreements with USN it's reasonable to expect that technology between these two navys will continue This may see DEW, Hypersonic and Counter-Hypersonic Weapons systems being integrated on the T83 alongside continued development in the Electronic and Network-centric warfare systems being shared between the two forces. This will inevitably lead to a growing reliance on data network integrity both in-ship and between ships in a joint NATO fleet.

“The next decade is likely to see a ‘Dreadnought moment’ in relation to war at sea stimulated by radically novel technologies. Despite its massive superiority, the US will have to continue to invest heavily to maintain its lead while other ambitious navies, notably China and Russia are likely to follow closely. The rest will struggle to remain within touching distance, especially as they doggedly persist with traditional ship programmes and designs well into the future. As a result, the world will be divided into countries that can prevail at sea and those that, frankly, need not bother”

Rear Admiral Chris Parry, RN Retd, speaking to Royal United Services Institute, Mar 2021

(Reference)

The Challenge of the Design

Details of the Type 83 are not publically available; however, conclusions can be drawn from the Type 45.

Although considered the most capable Destroyer in the world today, the weaknesses in the Type 45 are evident when considering it's layout and dependence on communications, both internal and external, and its reliance on electric propusion which distributes power and proplusion throughout the ship.

The role of Destroyers are to act as a shield, which involves being deployed up-threat, defending against and if necessary taking strikes from an incoming attack in order for the main Task Group, generally in the RN's case a Task Group centred on a Queen Elizabeth class Aircraft Carrier, to continue on-task.

As such, a Destroyer's task in a battle situation tends to be one where it is likely to be the first to sustain damage, but who's role is to continue to prevent damage to the main fleet regardless of damage sustained to itself. Should that fail, removing a Destroyer as an effective platform leverages the ability of the enemy to prosecute the engagement on the primary target far more effectively.

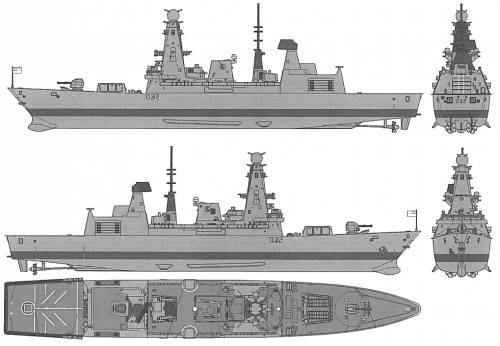

As an example, consider the layout of the Type 45:

A majority of the hardware necessary to continue that comms and data transmission is centralised above the water-line in the main super-structure. Not shown here are two server clusters, one forward, one aft. However, both serve the main super-structure island.

The vulnerability is then that a powerful and effective platform may be rendered ineffective by a single missile striking midships, a rather likely situation should any missile strike get through.

Because of this Destroyer design focus has been on prevention of that strike - on the effective deployment of CIWS for example. However, technology has not been forthcoming that would allow such a sophisticated ship to continue fighting beyond that first strike.

Contrast this with the designs available during WW2, where it was not unusual for a Heavy Cruiser (the equivalent size of vessel then) to sustain several sustained hits and continue fighting.

Warships now are therefore now generally both far more lethal and far more fragile than 80 years ago.

In terms of ROI, each T45 has cost roughly £1.050 billion to build. Typically 2 would be deployed defending a Queen Elizabeth Class aircraft carrier (cost £3 billion). With additional Frigates for anti-submarine warfare, a Task Group, who's ability to project force lies primarily with the aircraft carrier, may well cost £10 billion+.

Should a T45 be disabled by a single missile strike and be unable to continue its mission the Task Group would be exposed on that side making a strike on the primary target more probable. Should that happen the total cost would be roughly £1bn + £3bn + loss of capability in the current campaign (ignoring of course the human life involved.)

If a T45 could continue to protect the capital ship following a single missile strike, even if subsequently it needs to return to port, then that cost reduces to £1bn, with far fewer casualties.

Given the current Chinese and Russian military doctrine of combatting missile defences through massed strikes, it's probable that more than one anti-ship missile will get through. If the Destroyer continues to be available the cost remains static until that ship can no longer provide the cover to the capital ship. It's dependent therefore on the scenario whether the enemy has sufficient incoming ordnance to acheive it's aim. However, it's certain that a Destroyer that can continue to fight beyond a single missile strike damage is significantly more valuable that one that cannot.

Strategic Intent of this Request

Provide a data comms and processing capability that can be deployed on a warship at sea, with the expectation that it can survive one or more strikes from an Anti-ship or Cruise missile and continue on-task, where 'survive' is defined as the abilty to continue providing a platform for those weapon systems that have locally survived the strike but which depend on non-local data connections and therefore control.

Moreover, it should be robust in normal peace-time use (minimising the need for specialist repair.)

Tactical Intent

To do this, we need to:

- Maintain normal operations in peace time while minimising the need for specialist repair alongside due to component failure at sea.

- Continue the collection and dissemination of radar data, satelite communications data to the wider network-centric view of the fleet following a single missile strike.

- Allow the continuation of the 'external war' despite sustained damage.

- Allow the continuation of the 'internal war' - the damage control effort - despite sustained damage.

Detailed Description

Tactical Intent 1: Maintain normal operations in peace time while minimising the need for specialist repair alongside due to component failure at sea.

Must

- Be interoperable with all ship systems, many of which will be defined by others and may not have an API, routing instead through trusted network connections.

- Be air-gapped with the wider world.

Should

- Not require specialist software expertise while deployed at sea.

- Have a secure and auditable route for upgrades.

- Allow for Apps to be tamper-evident, and fail-safe

Could

- Provide rolling upgrades while at-sea without the need for maintenance alongside.

Should Not

- Allow any upgrades or alterations to the base operation without notification or requirement for authorisation.

Must not

- Introduce vulnerabilites in terms of attack vectors available to opposing forces.

Tactical Intent 2: Continue the collection and dissemination of radar data, satelite communications data to the wider network-centric view of the fleet following a single missile strike.

Must

- Allow verifiably correct data to be ingested by other nodes in the network or fail completely. I.e. the data gets through or it does not, there is no 'try'.

- Likewise, continue to receive and validate data from other platforms up to the point of failure, at which point failure is evident.

Should

- Continue contact through multiple routes, including satelite, UHF, VHF and Microwave connections, such that the signal gets through so long at at least one route is available.

Could

- Reduce the overall cost on-board of separate data systems requiring bespoke design and maintenance.

Should Not

- Degrade the jitter levels currently experienced on command signals, where jitter in-ship is roughly 2ms on-board and packet loss <1%. Latency is assumed owing to the short distances involved.

Tactical Intent 3: Allow the continuation of the 'external war' despite sustained damage.

Must

- Be capable of the Opps Room engaging incoming targets for self protection using at least one weapon system following a single missile strike which removes the comms room capability, assuming those weapon systems have not been locally compromised.

Should

- Provide a weapons platform for the protection of the Task Group, where those weapon systems and their operation have not been compromised.

Could

Should Not

Tactical Intent 4: Allow the continuation of the 'internal war' - the damage control effort - despite sustained damage.

Must

- Fail gracefully, in that assuming an on-going damage control effort onboard there may be an increasing degradation in the ship's ability to fight depending on the effectiveness of damage control efforts.

- Continue to provide internal communications between sections of the ship in order to direct Damage Control Teams and advise the chain of command of the current remaining capabilities of the ship.

Should

- Provide information on the minute-by-minute situation onboard following a strike to inform future ship design.